The summer and fall months can be ideal times to put on your hiking boots and take on one of the most iconic trails in Arizona - the challenging assent to the 12,633 feet summit of Humphreys Peak.

Credit: NPS

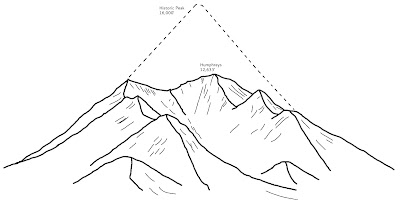

Humphreys Peak is one of six, volcanic mountains that together make up the magnificent San Francisco Mountain range just north of Flagstaff. Geologist believe that today's San Francisco Mountains are the remains of an ancient cinder cone whose main crater once rose over 16,000 feet above the local landscape. Some 200,000 to 400,000 years ago this mighty cone erupted in a thunderous roar resulting in the six lower peaks and volcanic landscape we see and enjoy today.

These six peaks are named and range in size from the tallest, Humphreys (12,633 ft), Agassiz (12,356 feet), Fremont (11,940 feet), Aubineau (11,818 feet), Rees (11,474 feet) and to the smallest, Doyle (11,464 feet). Some geologists argue that Rees Peak and Doyle Peak are actually false peaks whose prominences rise merely some 200 feet above the saddle of Aubinuau Peak.

Humphreys Peak has been known by many names over the centuries. The Navajo people call the mountains Dookʼoʼoosłííd) while the Hopi refer to them as Aaloosaktukwi and the Yavapai tribe calls them Wi:munakwa. During the Spanish Conquistador exploration of this region in the mid-1500s, the conquistadors named the mountains Sierra Sinagua which translate to mean “mountains without water.” In 1629 Spanish Franciscan Friars came into the area and renamed the volcanic mountains the San Francisco Mountains in honor of their patron saint, St Francis of Assisi. This was some 100 years before the Presidio of San Francisco was founded in northern California. But Humphreys - just where did the name Humphreys come from. Like so many place names in Arizona, the name Humphreys has a close association to the events of the American Civil War.

General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys was a career US Army officer, civil engineer and Union General in the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. His grandfather, Joshua, is credited as the “Father of the American Navy” as Joshua designed and oversaw the construction of the first six U.S. warships including the historic USS Constitution, better known as “Old Ironside.”

Young Andrew Humphreys first came to the Arizona Territory as a Captain of the U.S. Army Topographical Engineers and where he was assigned to the Joseph Christmas Ives Expedition (http://mojavedesert.net/people/ives/ ) of 1857 - 1858. This expedition became the first official U.S. Army reconnaissance group to see, document and explore the magnificent Grand Canyon while searching the northern section of the Arizona Territory for a possible trans-continental route for a railroad.

When the Civil War began, Captain Humphreys was assigned as an aide to General George McClellan as the Army of the Potomac’s chief topographical engineer. He was put in charge of the Union’s 5th Corps and led these soldiers through the Battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. But it was his engineering work at the Battle of Gettysburg that might be his most significant contribution to the preservation of the Union.

Captain Humphreys was transferred to the 1st Division of the 3rd Corps just before the July 1 - 3, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg. Upon his arrival at Gettysburg, Commanding General John Reynolds ordered Humphreys and his engineers to examine the topography of the Gettysburg area and make recommendations for the best offensive and defensive lines that the Army of the Potomac could form to stop the attack of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. This knowledge of the terrain and the resulting army placements proved to be a deciding factor in the Unions victory at Gettysburg.

Humphreys Monument at Gettysburg Credit: NPS

Captain Humphreys came out of these campaigns commonly acknowledged to be one of the most capable officers of the Union Army. On March 13, 1865 he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General of the U.S. Army “For gallant and Meritorious service at the Battle of Gettysburg.”

After the Civil War, Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys served as the U.S. Army's Chief of Engineers until his retirement on June 30, 1879. He died an American Hero in his Washington, D.C. home on December 27, 1883.

Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher

G.K. Gilbert - Credit: NPS

So what does all this have to do with our Humphreys Peak? The answer lies with Grove Karl Gilbert, better known as G.K. Gilbert, a famous American geologist who joined the John Wesley Powell Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region team as Powell’s primary assistant. It was while Gilbert was with the Powell Expedition that he found himself in the summer of 1873 in the ancient volcanic fields of the Northern Arizona Territory. He recognized that within the many volcanic cinder cones of this region, the tallest peak found in the Arizona Territory was located and that this peak needed an official, U.S. Government name. He thought a moment and decided to name this magnificent 12,633 ft peak Humphreys Peak*** after the Civil War American hero who just happened to also be his superior officer, Brigadier General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys.

Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher

***Prepare well when deciding the climb the trail to the summit of Humphreys Peak. Follow all common sense rules for hiking at a high altitude. Be sure to take plenty of drinking water as there is no fresh water on the trail. Good hiking shoes and appropriate clothing are a must - including a good hat. Do not attempt to climb Humphreys Peak if summer thunderstorms are over the summit or in the area. When you “Stand on Top of Arizona” you will truly be the tallest point in Arizona.